What the 🧨💥🤬 Is a Go-to-Market Strategy?

Clarifying the Meaning of One of the Most (Mis-)Used Concepts in SaaS

Hey, I’ve set a goal for myself with this newsletter. Naturally, an ambitious one.

I want to get 1000 subscribers by 1st July.

And you can help – by recommending it to your friends and peers. Would you?

And now back to our regular program…

Go-to-market strategy. Or just GTM.

Take a deep breath…

There’s hardly a more confusing term in business software.

People (mis-)use it when they want to talk about:

Product

Marketing

Product marketing

Can you post on social media when we release the new feature?

Is it all of these things? Kind of. (Definitely not the last one.)

Can we do a better job or defining and refining what it is?

Damn sure we can. Here it goes…

🥁 DRUMROLL 🥁

GTM = Marketing Strategy

Honestly, it shouldn’t be a revelation. It shouldn’t be controversial.

Because, if you try to forget for a second all the layers you have around the word, you will realize that go-to-market is just a definition for the verb marketing.

💡?

So go-to-market is just a fancy way of figuring out how to bring a product to market so that it finds and connects with the people who can benefit from it (and therefore would be happy to pay for it).

Why you should care about GTM even if you’ve made it

All of the above makes it sound like GTM is something that early-stage companies do.

You have an MVP, let’s figure out our GTM to go and find P/MF...

Fancy (SaaS) talk.

Here’s the (ugly) truth: Established companies suffer from GTM qualms just as often as tiny pre-P/MF startups.

Product pivots

Growing by building/acquiring additional tools

Market shifts

In fact, GTM can be even more important in the cases where a company has found success with one main product and is looking to expand with additional tools.

The combination of hubris and disposable revenue (fueled by the success of the main product) rarely makes for guaranteed success.

In the next few sections, I am going to share the framework I use when helping SaaS leaders nail down their GTM strategy.

A simple GTM framework

A good framework makes every concept more easily digestible. GTM is no exception.

My approach towards building a GTM leans heavily on the writing of Brian Balfour (and the Reforge gang in general). You can learn more about he calls The 4-Fits Framework on his website.

To formulate your GTM, you need to consider 4 elements:

Market: This is the group of people who have a defined problem and are looking for a solution for it.

Product: This is your (proposed) solution to the (set of) problem(s) the market has.

Distribution: This is how you will reach the defined market and connect them with the value of your product. (We often call this “marketing” or “sales”.)

Monetization: This is about creating a sustainable model that will allow you to stay in business. It’s not just about how much you charge, but also when, for what, and even if (think freemium).

We often hear people talk about P/MF, i.e. product/market fit, but in effect you need all 4 elements to be in alignment, otherwise you don’t have a sensible business strategy.

(A bit more about this at the end of the newsletter. Just to keep you reading...)

I’ll use one of my favorite products in the world Todoist to build a (rather crude) example of how companies sometimes get these (other) fits wrong.

Todoist is a low-ticket/mass-market product. If they decided to hire a Sales team to go and sell Todoist to 1-seat prosumers (which I imagine is the typical Todoist customer at the moment), they would have a very hard time turning profit (after spending on marketing to fill the pipeline for the sales team and paying everyone salary and commissions).

As I said the example is too simplistic and obvious, but I hope it helps you understand what having one element out of balance looks like. Plus, I’ve seen companies make even more obvious mistakes...

(Recently Todoist has launched a number of features which are essentially repositioning the tool as one for teams. It would be interesting to see how the distribution model evolves, i.e. whether they’re going to bring in a sales team.)

And the truth is that even one such imbalance can break your whole business before it’s even taken off the ground.

These 4 basic elements of GTM have been discussed in such great detail that I can probably think of at least one good book exploring each in detail.

Let’s start by reviewing each briefly (and I’ll leave a link to a good resource for each).

Market

I’m a firm believer that you should start with the market even in the cases where you already know what you’re building (for example if you’re “scratching your own itch”).

You might think I’m one for comically evident examples, but I’ve been on a customer call where I was touting the biggest product initiative of the company for the quarter only to hear from the customer (who was also a perfect aspirational ICP fit) that she didn’t care about it one bit.

Gulp.

Yes, these things do happen.

And they happen exactly when you’re building thinking you know the market.

Unfortunately, building without knowing the appropriate level of knowledge about your target customers is not that obvious.

In the example above, the product team in question was not building without doing research and talking to users. The problem was starting higher up – with the company not being laser-focuses on their target ICP and then leaving everyone (Product, Sales, Marketing) to fill the gaps for themselves.

The other classic mistake I see all the time (and not just in the very early-stage companies) is companies building without a narrow focus on the market.

It happens when founders get drunk on the feeling that they are delivering a huge innovation that everyone will want.

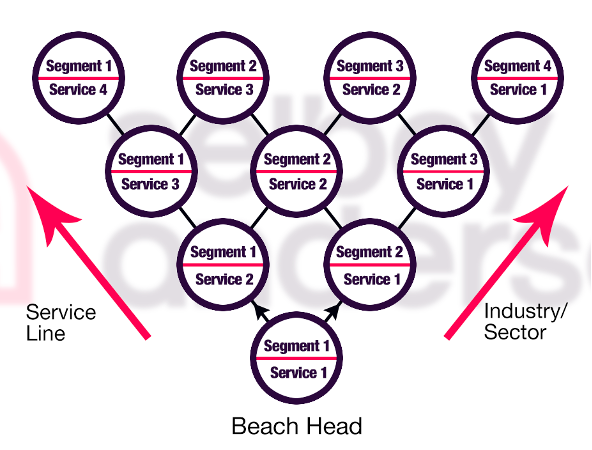

As Crossing the Chasm teaches us, there’s a thousand reasons why people avoid innovations and the only way to deliver one and win a market with it is by adopting what Geoffrey Moore calls “the bowling-pin strategy”.

How to narrow down?

I get it.

Every cell in your founder’s body screams against limiting the potential of your business.

However, starting narrow today, doesn’t mean staying narrow forever.

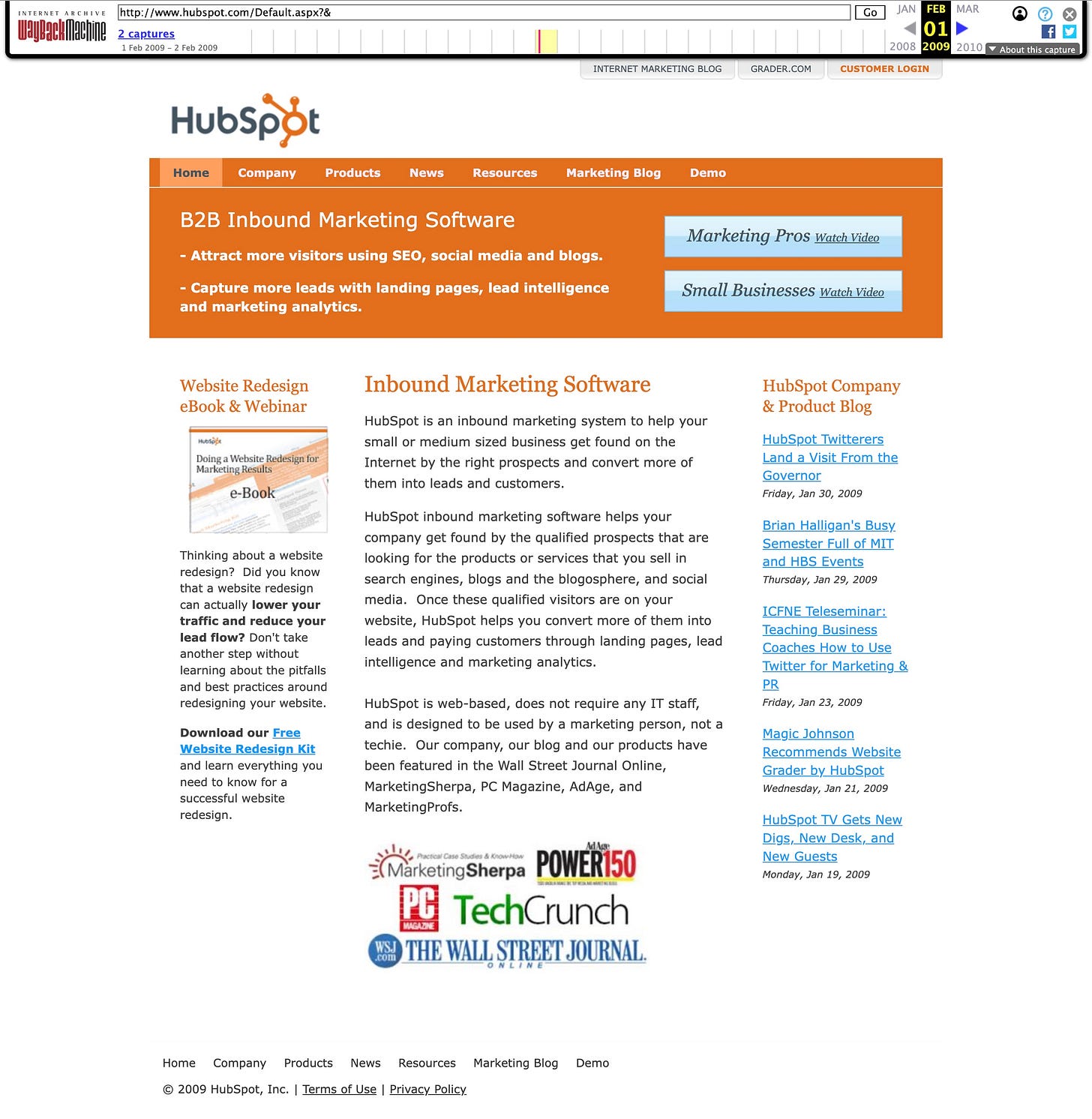

HubSpot started as an “inbound marketing software”.

Today it’s a behemoth, targeting every revenue-generating function (marketing, sales, cs) in what is the biggest market in the world – SMBs.

Whatever stage you’re in, you probably have a milestone in mind that you want to reach next. And that can serve as the starting point for how you narrow down in the short term.

Recently, I was talking to the founders of a startup that is targeting a huge market – over 1m e-commerce businesses. However, when we discussed their short-term goal and considered their monetization model, they realized they only needed to capture 1000 customers to hit that goal.

1000 out of a million gives you a lot of opportunity to narrow down and build something that would be just perfect for a tiny group.

Of course, once you’ve exhausted that, nothing stops you from widening your net and going after the next set of customers.

Recommended resources:

The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products that Win by Steve Blank

Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling High-Tech Products to Mainstream Customers by Geoffrey A. Moore

Product

Saying that you should do customer discovery is great, but it’s not so obvious what exactly that means.

The most important thing when doing it, is to unearth use cases, i.e. actual things your future customers was to do, that you can solve with a product.

There are numerous resources on what it means and how to build an MVP (minimum viable product), but the best thing I’ve seen on the topic is this:

What does it mean?

At every step of the development of your product, you need to be solving a customer need(/problem/challenge).

It can be just one (very) simple need, but your product needs to provide a complete solution to it before moving on to the next one.

Your investors care about the long-term vision, your customers care about what the product can do for them today.

However, it is also important to remember that you need to align the product with the market you’ve identified and set upon in the previous step.

To continue milking the example – if your target audience is F1 race drivers, you’re unlikely to be able to capture them with a scooter.

Although...

(Apparently scooters are great if you want to avoid pesky journalists…)

I realize I just countered destroyed my own argument, but this is a great example of how a defined market/target audience has different use cases that get served by completely different products.

Still, the point stands. If you’re building an HR software, it will likely look a lot different if you’re planning to go after SMBs vs. an enterprise market.

Building products is not my speciality and I do not want to spend too much time laboring the same point all over again, but there’s plenty of resources that go in more depth.

Recommended resources:

Distribution

Right away I want to make the distinction that Distribution does not mean talking only about channels.

That’s because distribution is a set of decisions that companies make that start before choosing what channels to pursue.

The most important strategic choice in distribution is what (set of) motion(s) to adopt to market your products.

Wait, what motions? 🤔

When it comes to software, there really are 3 ways to generate sales and revenue for your product. They are:

Product-led (or PLG)

Sales-assisted

Sales-led

Product-led growth is when you see companies grow organically, on the strength and virality of the product they build. PLG has becomes really popular in the last few years, but none of its poster children (think Atlassian, Slack, etc.) have stayed only with it.

On the contrary, we see, without an exception, that those specific success stories have all found ways to layer a sales motion (usually a sales-assisted one) on top of their product-led growth engine to continue growing and expanding.

On the other hand, we know of many companies who choose to stay sales-led (originally driven by the founder, but then handed off to a dedicated sales team) and who are equally successful.

The important thing to consider when choosing your motion strategy is to align it with the market and the product – in other words, we’re seeking market/distribution fit and product/distribution fit.

Slack is a simple product that everyone understands and can start using with relative ease. In addition, it can be used by a single team within a larger organization and gradually expanded to cover more divisions. Therefore, PLG served the team extremely well to land within the engineering teams of large companies and then expand (supported by a sales team) to capture the whole enterprise.

Has is served them well? Yes, provided Slack has over 100 customers paying over $1m a year!

A complex product that requires setting up, onboarding, and continued training that’s done by the whole organization at the same time is a lot different – you can still benefit from great UX, but don’t rely on PLG to drive your growth.

Take BambooHR as an example – it needs to be adopted by pushed (by an executive) to the whole organization to be useful. And that’s why they don’t waste any time with free trials or PLG and instead try to get you on a demo/sales call right away.

BambooHR is not the biggest HR software company in the world, but this approach has worked for them – their revenue is close to $300m per year.

Distribution Channels

Your motion strategy will influence the set of channels you choose to pursue.

A word of caution. Few Virtually no successful SaaS company has used a set of channels that all worked equally well.

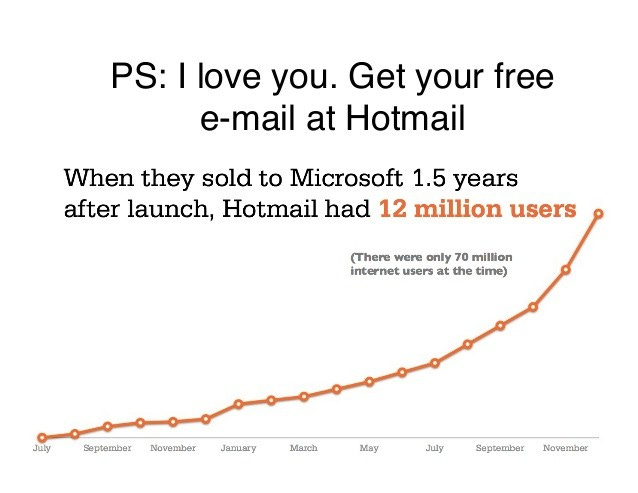

Usually, there’s one channel that comes to mind that is synonymous with the success of the company – for example, content for HubSpot, virality for Hotmail, and so on.

That’s because successful channels look and feel a lot like an avalanche.

In the Hotmail example above, every email sent generated more exposure for the product, which resulted in more signups, which in turn resulted in even more emails sent.

That’s why I preach the importance of aligning your motion strategy with the channels you are going to invest in and how you set them up.

If you’re planning on using a product-led motion, it’s likely you’ll want to invest in disseminating content organically, through strong SEO.

However, if you plan to rely entirely on sales, you’ll still need to produce content, but it will probably serve your sales team (i.e. sales enablement).

Hopefully, you see how this set of choices all align and influence each other. This process is what helps you avoid spreading yourself too thin, hoping you have a lucky strike in at least one channel.

Recommended resources:

Elena's Growth Scoop (perhaps the strongest voice on PLG)

Monetization

Please notice I’m not talking (just) about pricing (again, in this I’m heavily influenced by the Reforge team).

The price point you set for your product(s) – and with SaaS products, more often than not there’s more than one – is just one of the decisions you have to make about your monetization model.

So what other decisions are there to be made?

The elements are:

What are you going to charge for? This involves the ever-important question of value.

How often: Monthly, quarterly, annually? Discounting (for annual payment for example) often comes up in relation to this question.

Where: Are your customers just going to give you their credit card? What if they are a large enterprise customer who expects payment by invoice and/or NET30/60/90 terms? Technicalities, yes, but important ones that need to be considered in your process.

How much: Usually the decision about this comes last after you’ve decided all the other elements of the strategy.

The What: Question of Value

I want to pay special attention to the what part of the monetization strategy because it is the most important strategic decision founders need to make. And it goes beyond monetization strictly with implications for the whole business.

Thankfully, we’re past the years when SaaS companies charged per seat no matter whether their users needed seats at all.

As founders and execs started looking for ways to grow revenue from within (i.e. from existing customers), they often found out that often slapping a price tag on each additional seat did nothing for them.

(Often thanks to the proliferation of password sharing tools such as 1Pass and LastPass. 😉)

However, finding the right value metric is still elusive to many founders and more art than science to those who succeed.

Thanks to my work as an advisor and mentor, I talk to many founders and I often get asked about this idea of value-based pricing.

Introducing the product/monetization fit

You know when you have this one by the fact that customers are happy to pull out their cards when you ask them for payment.

Yes, it exists.

It’s rarer than a unicorn, but sometimes your customers instinctively know that the value they’ll get out of using the product is a multiple of what you’re asking them to pay.

(Especially if that multiple is in the 5-10x range.)

Finding the right monetization model can be daunting, but I promise you that it is possible. And there are tools to help you do it.

In the resources section below I will drop some ideas on how to learn more about the different types of research you can do. However, monetization as a whole is a big topic that I plan to revisit in detail in the future.

Resources

Monetizing Innovation: How Smart Companies Design the Product Around the Price by Madhavan Ramanujam & Georg Tacke (Read it!)

The 4 more like 6 fits towards a sustainable business

In his original post, Brian Balfour talks about “4 fits” that you need to find, to build a $100m business:

But in reality, you have the strongest potential and chance of succeeding if all the elements of your GTM are fitting with each other.

That means 6 fits.

And the 2 extra ones are quite obvious:

Market/Channel Fit: If you want to sell cake, the vitamin bar at the gym might not be the best place. You’ll probably have better luck at the local independent coffee shop. The channels you use have to be frequented by your audience.

Product/Monetization Fit: This is just a fancy way to talk about the need to align the value users get out of your product with the price they’re paying for it. You never want to be in a conversation where you quote your price and your potential customers smirks (or even worse, thinks it’s so low they don’t trust you can deliver a quality experience).

Companies can fail if they miss just 1-2 of those fits. Can you think of brilliant products that were missing a market. Google Glass?

Or those which rely on a channel/distribution model that will never make them sustainable in the long run. Blue Apron over-relying on paid distribution?

However, I can’t think of a single business that’s had all 6 fits and didn’t manage to survive. Feel free to tell me how wrong I am in the comments below.